| Assessing the strength and capacity of political and civil service systems in Central and Eastern Europe. The case of the Hungarian Ministry of Agriculture. (R.H.A.M. Knubben) |

| home | lijst scripties | contence | previous | next |

“It is unthinkable that politicians should be allowed to remove civil servants on grounds of incompetence. Of course some civil servants are incompetent, but not incompetent enough for a politician to notice. And if civil servants could remove politicians on grounds of incompetence it would empty the House of Commons, remove the Cabinet, and be the end of democracy and the beginning of responsible government." (Sir Humphrey Appleby, 1978)

Perhaps the quote above is a bit extreme in content, but it does show the antipathy between politicians and their respective civil servants. Both are needed, and yet both can be the sand causing the clockwork to grind to a halt. That is to say, if it was ever ticking in the first place.

‘Government’ is a word too often misused and abused. It implies an entire structure without making any distinction between the units that make up this mythical monster. It ignores how they operate in conjunction, and is blind to official chains of command and invisible balances of power. Generalizations smudge the nuances that make all the differences in the world, sometimes a blurred vision is worse than none at all. Cyclops may rule the land of the blind, whether he is any good at it is a different story.

This research project started out with a relatively simple task, do a comparative analysis on the performance of the Hungarian ministry of agricultural over a certain period of time. Consequently, the initial hypothesis was phrased as follows:

The ineffectiveness of government policies is partly caused by a combination of economic, political and institutional weaknesses. This has to be unified with the legacy of the (socialist) past on behavior, and the scope of opportunities in the increasingly market oriented present (continuity).

Economists often overlook the institutional framework and rule of law, whereas legal scholars make the same mistake in reverse. Students of public administration do capture the sociological and institutional elements, but don’t pay enough attention to economic theory and the big picture in general. This way all three professions in their own way seem to lose track of reality, and retreat into their world of convenient theoretical propositions. It is the author’s belief that all factors matter, be it on a varying level, and they should all be taken into account (Knubben, 2002). The mostly explanatory nature of the research question requires to give way of a certain building logic. In other words, a causal chain aX1+bX2+…+…=Y should be established.

Following months of research in Budapest, the approach has somewhat shifted from a focus on specific policies to the strength of civil service systems as a whole. Strength should be perceived as the aggregate capacity of all ministries combined, the ‘political capacity’ and ‘the power of institutions’. The development of a new framework was induced by the apparent inappropriateness of existing theories and unreliability of many commonly cited publications. The most prevailing theories on assessing the strength and nature of a civil service system have been developed by:

Morgan (1996), analyzing fields of change: civil service systems in developing countries, civil service systems in comparative perspective, Bloomington, Indiana University Press

Heady (1996), configuration of civil service systems, service systems in comparative perspective, Bloomington, Indiana University Press

Worldbank, World development report 2003, sustainable development in a dynamic world, Transforming institutions, growth and quality of life

Figure 1: Worldbank model on relationship between social capital, institutions and organizations

Source: Worldbank, World development report 2003; sustainable development in a dynamic world

To a lesser extent one can also find references to Raadschelder and Rutgers, civil service systems in comparative perspective (1996) and works by Christopher Hood. Most research using these theories does have its strong points, but also incorporates a number of crucial drawbacks that diminish validity. It assesses the functioning of a civil service system as a whole, making no distinction between the separate units of the state apparatus such as ministries. Furthermore, it is usually based on official documents released by the government, or written by ‘recognized experts’ on a country who are often aligned to a political party. Hungary is no exception in this respect. It is what the author would like to call the apparent vs. actual reality dichotomy.

Tackling the problem of unreliable data and reports is not an easy feat to accomplish. The only real solution is to engage in fieldwork, implying many interviews with those who DO know, be it on or off the record. In the case of Hungary, it is quite hard to find a mid or high level bureaucrat who is knowledgeable and acquired his position thanks to his expertise. Secondly, this person has to be able to speak at least one familiar foreign language. Most importantly however, the official has to be willing to speak out and give his vision without fear of retribution.

Chapter 1 introduces the basic framework that will be used as a guiding wire. It explains its functioning, shows the relationship between the variables and provides ample theoretical grounding to validate their usage. Chapter 2, 3 and 4 explain in depth the model’s 3 main components, being respectively ministerial capacity, political capacity and structural & assessment factors. These will then be applied to the Hungary of the past and the present, showing a clear development over time. Finally, the conclusion will follow in chapter 5.

This thesis has to a large extent been based on interviews with a substantial amount of mid and top level officials at the Hungarian ministry of agriculture & Regional Development (MARD), and the Agricultural intervention center (AIC). The Dutch embassy to Hungary has also provided ample aid, spawning a large expert staff with relation to the topic of research. The EU mission to Hungary and the French embassy, together with a number of professors related to BUESPA have completed the picture as far as local sources are concerned.

External evaluations have been provided by a number of officials at the Dutch ministry of Economics, and a group of professors employed at Maastricht University, Catholic University of Leuven and Brandeis University in Boston. The framework that will be presented is the result of all findings combined, striving to find a middle ground between different opinions. In the end it is the author’s personal interpretation of facts that has created the final shape. It should also be mentioned that most officials used as sources in Hungary, would prefer to remain anonymous. A list of those sources will only be provided to the thesis promoter, and remain strictly confidential.

§1.1 Background

Within the realm of PA many important issues are overlooked, or at least not combined into one comprehensive model. Obviously this can be said about any number of disciplines, nonetheless the practical difficulties encountered were significant. In order to cope with this a new list of factors - whose usage has been validated by the findings of the investigation at the MARD - was created. From there on the model has been extended to assess an entire civil service system, specifically aimed at transition countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

The main premise is that the ability to transform a country in this region depends on political willingness within the government, political willingness within the relevant ministries, the power of the ‘trias juridica’ and the CAPACITY to create, enforce and monitor policy. The trias juridica refers to the symbiotic relationship between the public prosecutor, the judge and the enforcement system (police). In order to give an assessment, one needs to decide what the ‘ideal type’ situation would have to be.

Furthermore, the socialist heritage of the last 50 years cannot be designated as the sole culprit for many of the transition countries’ current problems. The notion that socialism simply provided a different flavor to centuries of authoritarian rule is an interesting one, and often overlooked. As will be shown with agriculture, structural causes of some of the difficulties date back one and a half centuries ago. From a productivity perspective, it can be argued the socialist restructuring even benefited the country, rather than the opposite. Collectivization most certainly did lead to economies of scale. “That it was implemented harshly, with minimal flexibility, and in the context of a command economy is a different question” (Swain, 1999). This benefit of the CMEA days is unfortunately today’s ghost of the past, a blatant disregard for quality and efficiency in return for overproduction of goods, quite the irony.

Finally, the damage that was done AFTER transition during the nineties as a result of incompetent political leadership and poor policy making, may turn out to be more significant than the last 30 years of socialism.

§1.2 Benchmarks

Since the focus is on Eastern and Central Europe, the ability to meet the Copenhagen criteria should serve as a relatively decent benchmark. Thus, if a country is able to reach the objective within the relatively broad context, which the EU Commission has allowed, it should count as a positive development. In other words, full privatization is not by definition a must if historical heritage or the current political situation would favor a slightly different approach. Results outweigh approach; hence the Washington consensus will not by definition yield the right solution. As far as the civil service is concerned, a Weberian model of a professional independent staff still seems to be the ultimate goal (Weber, 1866), albeit with some adaptations. The civil servants should not merely enforce orders; they should operate as a group of experts. Apart from having operational expertise they should also be able to make policy suggestions, create policy within a given mandate and confront the ‘political officer’ in case of disagreement.

Being far away from debates on e-governance or backlashes of New Public Management, “the crucial issue in the region is not to redesign, but to establish an independent, neutral civil service[…] the difficulties related to the transition coupled with the tasks of institution and market building place extraordinary pressure on the management and workforce in the public sector” (Jenei, 1998). Sharing the author’s view on an adapted Weberian model, Jenei states that CEE needs civil servants who “can be paternalistic or protective as required, but can also work as a partner and efficient manager, and who possesses personal integrity and independence from the political process”.

If the capacity is in place with both the government and the ministries, the ministries themselves should be able to handle the ‘key policies’ within their respective fields. The ministry of agriculture would handle the reform of the agricultural subsidies and issues related to land restitution, finance deals with tax reforms whereas the ministry of justice implements the acquis. The aim is to evaluate the findings for each factor. The aggregate of each ministry would reflect the ability to handle the key policies and ministerial capacity.

The combined grade of all ministries would therefore comprise all governmental functions and duties. The thesis does not specifically mention how all normative evaluations should be quantified, in order to create a statistical model. Some suggestions are made, but future research is required and it would have been impossible to include a comprehensive set of algorithms at this time.

Since all transition countries in the region are faced with similar problems, each ministry is given equal importance, equal weight. Therefore, if a government would chose to ‘strategically neglect’ the development of a certain ministry, this would result into a lowering of the grade. In reverse, strategic emphasis would increase it. For all other factors a merit based system would work best, probably within a 1 to 4 scale. Eventually the aggregate grade of the ministries is combined with the grade for ‘political capacity’, leading to a final appreciation. In case ministries are called differently when doing analysis between countries, the functional comparison should be used. To reduce complexity, only the most relevant functions are worth looking at. These would be economics, finance, justice, agriculture, education, interior and external affairs. Defense would be of less importance, although NATO membership does require developments in this area as well. Sometimes non ministerial organizations which in effect really perform functions related to the ministry SHOULD be considered to be part of the organization. The AIC and Hungarian agriculture council belong to this class of entities.

Per year the model would be able to give a single appreciation for the PA capacity of a transition country. Progress of a country can be shown over time, and also a comparative analysis between different countries will be possible. The final grade will be related to a comprehensive set of assessment indicators, ranging from technological development to societal acceptance of policies.

Figure 1.1: The augmented Solow model

Source: MIT, Economics 202a, Fall Lecture 3: Solow Model II Handout, 2003

K = total capital k = capital per worker (K/L)

L = total labor s= savings rate

Q = total output q = output per worker

n = pop. Growth б = depreciation

α = technology coefficient

In order to assess the relationship between technological and economic development the augmented Solow (1956) model is still valid.

Savings equals Investments, which is represented as sq = (n+δ)k. The black striped line in the picture represents the total amount of investments in an economy, which crosses with the savings function sq on the grey line. The red and blue lines denote the output per worker as q = αf(k). An increase in population growth n WILL lead to a higher q, but only on its given function. As the functions will eventually approximate a 0 degree angle, this is not a viable approach for the future. The only way to achieve significant gains in terms of economic development is to change the technology coefficient of the output model, α. This should constitute a jump from the blue to the red line, leading to a much higher q. When applied to the propositions of this research, the model’s main premise would be that an increase in ‘capacity’ will lead to technology jumps and consequently increase macro economic performance.

At BUESPA Attila Chikán has developed a multi dimensional comprehensive analysis with respect to Hungary’s competitiveness, defining it in both macro and micro economic context (2002).

“We may consider enterprises to be competitive if they are able to transform available resources into a profit flow while complying with the social values of the environment in which they operate, and if they are able to perceive and manage external and internal changes that influence their long-run operation in order to maintain their profitability, entering long-term survival [….] The competitiveness of a national economy is the ability of a nation to create, produce, distribute and provide products and services that meet the requirements of international trade so that in the process the return on its own factors of production increase.”

In the new framework that will be introduced shortly, the outside world can pressure the central government, but also deal with the ministries directly. When this occurs the ‘factors’ have been slotted with ministerial capacity. Clearly this will create a correlation between political and ministerial capacity, as can be seen in figure 3 on the following page. The handling of key policies has its reflection on society as a whole, which can respond by using democratic tools just as general elections. Another important factor however is public scrutiny. Basically it shows the public’s ability to disseminate information on governmental performance, and consequently create pressure by means of a feedback mechanism. Lobby groups are considered to be operating more from within the model.

Finally, a factor of ‘resourcefulness’ has been added. Of a highly controversial nature, true, yet not something easily to be discarded. Over the last 2 centuries, a number of transition countries have been consistently more responsive to changes and shown greater entrepreneurial spirit than others. In comparison, Hungary would easily beat Romania. How to incorporate this into a model is a totally different question , something that will require a great deal of thought.

Figure 1.2: Assessment model

§1.3 Introducing the model

Once again, it should be stressed that the research performed primarily deals with changes related to the MARD and its policies within Hungary. The model was initially designed for this purpose alone, and although the theoretical extension for the ‘overall assessment’ was a logical result, it was created at a later stage. Because of this, the model can only partially be completed since the in depth knowledge that is required for assessing the other ministries is lacking. It would take a knowledgeable research team with access to all sources to paint the picture with all variables involved. Thus it should be perceived as a guideline for future research within the fields of economics, public administration and law.

That being said, some ministries other than agriculture did receive special attention, both through literature sources and interviews with diplomats and government officials. Without this input, it would not have been possible to conclude how very different the political and structural situation with respect to different ministries actually is. The following tables introduce the variables that serve as the basic foundation for the entire research project.

|

Political capacity |

|

(1) Degree of polarization |

|

(2) Strong leader |

|

(3) Nat. identity & cultural awareness |

|

Ministerial capacity |

|

Internal factors: |

|

(1) Historical development & loyalty |

|

(2) Organizational structure |

|

(3) Effective policy-making |

|

(4) Tradition & culture |

|

(5) Prestige, staffing & funding |

|

(6) Degree of polarization |

|

(7) Corruption externalities |

|

(8) External influence factors |

|

Other structural factors |

|

(1) Power of judiciary |

|

(2) Public scrutiny |

|

(3) Resourcefulness |

|

(x) Assessment indicators |

§1.4 Integration

The factors that have been introduced incorporate the four classification parameters that can also be found with Morgan and Perry (1988) and Heady (1996). These are rules (“assigned guides for conduct or constraints that social systems use to structure behavior”), structure (“the organizational arrangements of civil service systems”), roles (“the set of activities expected of a person occupying a particular social position”), and norms (“values internal to the system which ground the rules and roles”). Clearly the variables in Heady’s configuration scheme will all be reflected, yet taking a more in depth and structural perspective.

Table 1.2: Main variables of Heady’s configuration scheme

|

Relation to political regime |

|

Socioeconomic context |

|

Focus for personnel management |

|

Qualification requirements |

|

Sense of mission |

As part of the OECD Sigma project, Les Metcalfe, currently professor at European university in Florence wrote ‘meeting the challenges of accession’ (1998). He stressed that the capacities required to make EU policies work range from operational management capacities to expert knowledge in certain fields (e.g. agriculture), and the ability to make crucial policy choices and enforce them. Furthermore,

“Thinking particularly about the approach of CEECs to accession negotiations, it becomes clear that it is vitally important to keep in mind another type of capacity that is crucially important and in extremely short supply: capacity building capacities. As well as knowing what kinds of capacities are needed to gear national administrations up to the task of EU accession[…] it is essential to know how to build and develop those capacities.”

§1.5 Theoretical grounding

The framework itself draws heavily on neo-institutionalist theories. To quote Douglass North, “The institutional approach defines institutions as the indispensable framework within which human interaction takes place--as the "rules of the game," the humanly devised constraints, that determine incentives and shape human interactions in all societies (North, 1990:3-4). Some institutions, such as laws, tax regimes, and the explicit operating rules of organizations, are formal, while others, such as cultural norms and established conventions, are informal. Formal rules are only a small subset of the constraints that govern choices and human interaction, while informal constraints and conventions are so pervasive that one is often misled into underestimating their role and importance. Institutions, both formal and informal, reduce uncertainty, structure incentives, define property rights, limit choices, and ultimately determine transaction costs” (North, 1990). He especially finds that within transition economies, transaction costs are extraordinarily high, and a time/learning curve can be constructed for both the public and private sector. Each country adapts at its own speed, following a different pattern.

Related to this is Elster’s (1994) matrix, which shows how constitutionalism (power of institutions) can be a stimulus for economic performance.

Table 1.1: Elster’s matrix denoting relationship between institutions and security & economic performance

|

|

Security |

Efficiency |

|

Civil and political rights |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

|

Government structure |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

|

Constitutionalism |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

a) Civil & political b) Social c) Economic |

Source: Elster (1994)

In short, the mechanisms that mediate between constitutional enforcement and economic performance are:

Accountability: Politicians are held responsible for their actions, this affects both security and efficiency

Stability: The constitution should serve as a beacon, which is free from political manipulation. Rent seeking is discouraged and basic rights are safeguarded. The relation to accountability is clear.

Predictability: Long term planning will only really be possible when citizens have faith in the system, and can expect a certain type of reactions from the government. Issues such a retroactive legislation and expropriation are most certainly not helpful from this perspective.

Protection against time inconsistency: The basic regulatory framework serves as a form of pre-commitment.

John Elster is an adept of Knut Wicksell, whose seminal 1896 work recognized the importance of the rules within which political agents make choices. Efforts at reform must be directed towards changing the functioning of the decision making process. This runs contrary to the concept of Pareto allocation which neglects the before mentioned issues.

The interplay between the domestic and external world is based on International Political Economy’s theory of Second Image Reversed, a two-level actor games with a Nash equilibrium as starting point. Studies of domestic politics have shown that changes in the international structure do not always lead to changes in the foreign economic behavior of states. Domestic institutional inertia may upset the power balance between domestic actors, and block policy changes. Second Image Reversed was developed to take precisely this into account, with Robert Putnam (1988) and Helen Milner (1988) as its founders.

Figure 1.3: Two-level actor game

At level one, the world of structural realism, there are interactions between international actors. At level two, the world of domestic politics, negotiators are accountable to a wider internal audience. The logic of the two-level game can be defined in the following way. At the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favorable policies, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign development. The game implies that the possibility of agreement is limited to overlaps of what is acceptable to the winning coalitions (level 2 game) in each of the parties in the negotiation (level 1 game).

Finally, theories that were introduced by Michel Crozier and Erhard Friedberg are extremely helpful to trace social processes and political structures. By looking at how people really act when solving conflicts and problems of public interest, one discovers the power structures that constitute the context for the actors involved. The actors build and uphold social structures that in turn offer a rationale for their behaviour. “Even more important, individuals' short-run responses to economic and political change depend heavily on their societies' inherited, and often entrenched, institutional arrangements. Their responses may be constrained or facilitated by patron-client networks, ethnic and religious solidarities, organized access to government resources, incentives for short-term profit taking rather than long-term investment, and social structures that facilitate the evasion of taxes. Therefore, actual behavior provides crucial information about institutional constraints on the array of possible choices and policies” (Crozier, 1977).

Crozier’s approach can be combined with that of Pierre Bourdieu, who says that “Evaluating the conduct of public agents and the functioning of the state structure in terms of ethics can be carried out according to the following: the ethical vacuum, where decision-makers do not answer for their actions and there is impunity; the ethical duality, where an idea is predicated but at the same time ignored or counteracted in practice, and minimal ethics of a reactive nature, based on convenience” (Bourdieu, 1998).

§2.1 (1) Historical development & loyalty

The present is history in the making, thus history is the present of the past. To understand an evolutionary process, it is imperative to find its starting point, the earthquake that defined the amplitude and direction of the tremor. Even though it may appear to be a sign of over-zealousness to go back as far as the Middle Ages, this is exactly where the story commences.

The ministry of agriculture was created after the 1867 Compromise, hailing the creation of the Dual monarchy. Next to a commonly regulated military and foreign policy it allowed for reasonably independent policies in certain fields. It is one of the oldest ministries in Hungary, created and modeled after the Weberian administrative model, which was dominant in the Austro-Hungarian empire.

The top of the ministry has always aligned itself with the prevailing forces, or rather the prevailing forces have shown the tendency of filling the ranks with their own kind. Up to the inter-bellum period, the middle and upper cadre showed a clear affiliation with the nobility. This ruling elite had guided Hungary’s agricultural development from its early inception onwards. Where in the 15th and 16th century most Western European countries were engaged with constitutional changes, Hungary lapsed into the 2nd serfdom (Swain, 1999). A large agricultural population with the ability to export foodstuffs to the importing Western markets induced this strategy. On the longer term however, it only increased the country’s backwardness. Under Maria-Theresa a regional specialization program was set-up within the empire, designating Hungary for mostly agricultural production. Again, it was the nobility’s influence that solidified this strategy with the Treaty of Szatmar. It arranged the protection of Austrian industry with internal tariff barriers, yet agriculture was left relatively unprotected.

In 1853 serfdom was abolished, though over 60 percent of the land remained in the hands of the nobility. The ministry re-enforced these power structures through the granting of subsidies and encouraging cartelization. As late as 1895, the land division was as follows:

Figure 2.1: land distribution in Hungary 1895

Source: Berend and Ranki (1974)

Up to World War One the large land holdings (Latifundia) increased, whereas the pressure only grew larger on middle sized landowners. The land reforms in the 20’s had a minor effect on the structures in place, as some 250,000 landless peasants were allotted not quite one hectare each. High world agricultural prices combined with capital imports boosted the sector, however this process abruptly ended with the 1929 stock market crash.

In the 30’s Hungary’s economy converged increasingly with that of the German Reich, leading to a 1934 agreement that granted favorable prices for Hungarian agricultural exports. The increased influence of the Third Reich entailed serious consequences, including a very unpleasant reclamation of Jewish lands (Pók, 1996). Suffice it to say that during the socialist period the middle and upper cadres were filled with officials loyal to the party.

This trend has continued during the decade after the transition, involving increased polarization on the political scene. §2.6(6) will deal with this in much greater detail. Political responsiveness and regime loyalty do not necessarily have to be a bad thing, provided the powers that be have the willingness and expertise to create decent policies. In any case, a high degree of loyalty will most likely diminish a ministry’s own input and policy making capabilities (§2.3(3)). If the problem is consistent and structural it will negatively affect the strength of a PA system. Ideally a civil service system would be able to function and perform all of its duties, even during times of political impasse.

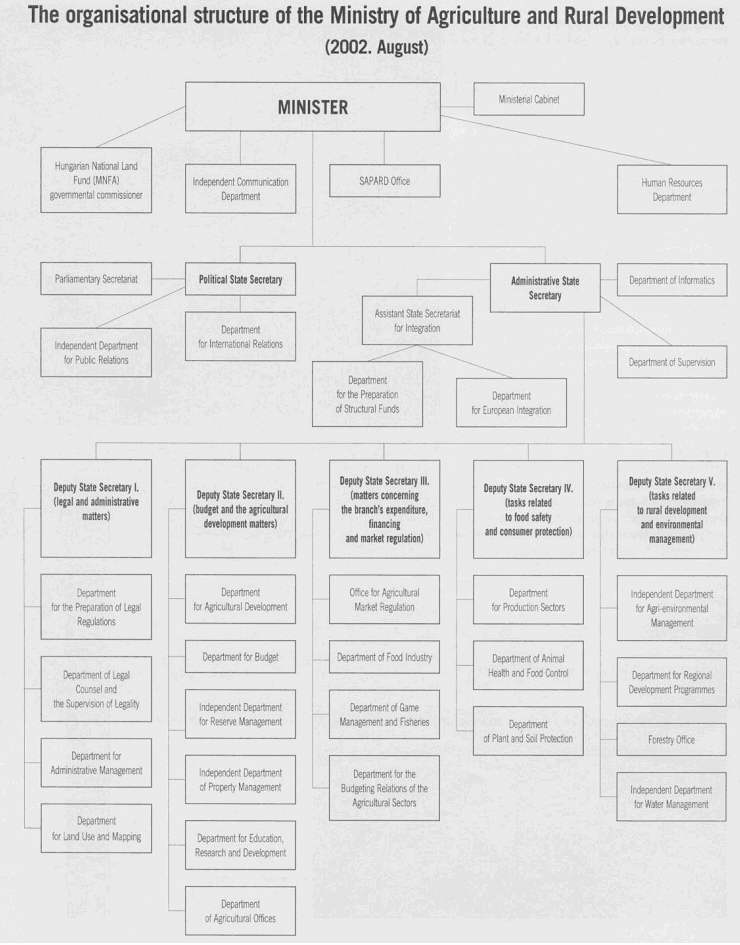

§2.2 (2) Organizational structure

Ever since the ministry’s inception the basic operations along functional lines have remained the same, although upper and middle management systems have changed throughout the years. These are the departments related to legal & administrative matters, budget & agricultural development matters, rural development & environmental Management, finance & market regulations and food safety (MARD, 2003). The entire structure was created and essentially still functions as an administrative enforcement mechanism, implementing policies from higher hand.

A system of a political and administrative state secretary was introduced after the transition, copying the UK model. The political state secretary deals with the parliament and other political affairs, whereas the administrative secretary is supposed to control the bureaucratic apparatus. Intended as a non-affiliated longer term technocratic position, Hungarian politics has nonetheless brought it to realm of party politics. Indeed, it does not help a proper functioning of the system.

From reliable government sources it has been made clear that the animosity between the two state secretaries at times prevents any proper decision-making. To add insult to injury, mid and high level department heads are usually unaware of the exact number of sub-departments for which they are responsible. The author has personally experienced a 45 minute long debate between two department heads, regarding which sub departments fell within their respective responsibilities in that particular week. In the end, no conclusive answer could be given to an apparently simple question. The organizational charts of the ministry of agriculture can be found on the next pages. Note the differences between them, with figure 2.2 being an internal document, and figure 2.3 the official scheme intended for external use. Neither of the documents are correct.

At its inception the SAPARD office had been incorporated within MARD (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development), as was mandated by the EU. The departments for European integration and ‘preparation for structural funds’ were related to this, though not in a strict hierarchical sense (Commission, 2002). What is more interesting however, is what could NOT be found on the official organization chart.

The Agricultural Intervention Center (AIC) was set up in 1998 and had been designated as the paying agency for the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee

Figure 2.2: Organizational chart of the MARD

click to enlarge

Source: Internal MARD document

Figure 2.3: The organizational structure of the MARD

Source: The Hungarian Agriculture and Food Industry in Figures, 2002

Fund (EAGGF). Its function was to disperse the CAP subsidies, and enforce all other related policies such as designating which 10% of the arable lands should not be used for cultivation. It was supposed to be the farmers’ first contact point and source of information. Its functioning will be discussed in detail in the next section.

The Hungarian Agricultural Chamber is a private non-government foundation, which acts as the strongest representative of the agro-industry. Only the largest producers in the country are represented in this group. In an issue of Business Hungary (2000) the deputy secretary of the chamber was quoted, “Meanwhile, farmers are excluded from directly influencing the market… those who should ensure a strong market and guaranteed prices for products do not take the required responsibility in the issue.” These types of complaints can be found in any of their publications, yet what cannot be found in any public resource is the chamber’s involvement with foreign trade policies. For example, the current minister and state secretary both used to hold leading positions within this organization, hence there is a very strong link and possible conflict of interest.

Apart from the core that has existed from the beginning, there is much that doesn’t meet the eye, drastically reducing transparency of structure and procedures.

§2.3 (3) Effective policy-making

§2.3.1 (3) Background

Effective-policy making has never really been the main focus of the ministry. The situation before the war has already been explained in factor (1), moreover its influence only reduced during the following 50 years. The national planning office would set the prices and subsidies for agricultural produce, which would then have to be approved by the central committee. Subsequently the directives would be sent to the prime minister, who would afterwards refer it down to the ministries. During the last 20 years of socialism the national planning office increasingly relied on the aid of its research agencies. These consisted out of rather A-political highly qualified technocrats, who would obviously consult with all parties involved before issuing new plans (Jenei, 2003). This was a clear signal for ministries such as finance to increase their influence on the economic process, yet this was definitely not the case for agriculture.

The ‘free’ co-operatives simply received the designated subsidies, and the maintenance of the ‘price scissors’ was out of the ministry’s control. This policy introduced under the Kádár regime intentionally put a huge burden on the agricultural sector. Although prices of agricultural products were liberalized somewhat after 1968, they nevertheless were kept artificially low. On the other hand, industrial input prices remained at a much higher level. This way agricultural profits were redistributed from one part of the economy to another. The foreign currency export gains were only partially remitted to the sector, which essentially created a double burden. Why, because the export subsidies did not match the total amount flowing into the state budget. “The net effect of these taxation policies was to starve agriculture of the capital necessary to maintain its performance, and the sector entered a deepening crisis by the late 1980s” (Benedek, 1998)

All of this happened simultaneously with the emergence of a smaller private sector, following the 1968 golden parcel rule. From a technical point of view land was still privately owned by farmers. ‘Voluntarily’ it was pooled together in order to produce for the co-operatives. During the period ‘67-‘68 the law on land reform ordered that apart from a small private plot which could be sold as well, the co-operatives themselves would own the land. The draining of the agricultural sector had caused many citizens to move to the cities, which conveniently caused the government to declare “that 'outside owners', who were no longer members (because the did not fulfill the minimum work requirements for membership), were obliged to sell” (Swain, 1999).

The ability for former landowners to use this small plot for private production is perceived as one of the big engines behind the sector’s success in the 70’s and early 80’s. Essentially it was an integration of large-scale and small-scale agriculture, where small-scale 'family labor' connected with large-scale wage-labor employing ventures. Part of this success can be attributed to the free use of input materials and machinery from the co-operatives, whilst the profits gained were accounted for as private income.

The current situation unfortunately has not improved. Hungary’s annual estimated agricultural production value amounts up to about 2000 billion Forint, to which roughly another 240 billion is added in the form of subsidies (Dutch Embassy, 2003). At present that amount is insufficient to even maintain the status quo. Throughout the 90’s the amount of state subsidies have not been kept in correlation with inflation or the increased financial burden facing agriculture.

Extra costs such as land lease and service fees were added after the land reforms, thus increasing the cost structure. All of this has created a significant widening gap between input and output prices to state subsidies. Udovecz (2003) at the Research and Information Institute for Agricultural Economics in Budapest states “The large delay in the closing up of the prices was allowed by the simulated "neutrality" of state authorities (market and competition regulation!) and the market actors’ unwillingness to cooperate[….]Consequently, economic policy decisions taken or postponed in this period induced such a loss that the sector has not been able to overcome”. The agricultural chamber whose relation to the government has been explained before, to a large extent makes up these ‘unwilling’ market actors.

§2.3.2 (3) 90’s to the present

That these subsidy structures will change, and issued according to the CAP guidelines is not very well known by the farming population. Of those who DO know, only few realize that for the first year they will only receive at maximum 30% of the direct payments, compared to what would be the support for the EU 15 (Agrafood, 2002).

|

Table 2.1: Phasing-in schedule for direct aid payments in new member states |

|||

|

Year |

EU aids (% of full EU rate) |

National top-up (% of full EU rate) |

Overall max. payment (% of full EU rate) |

|

2004 |

25 |

30 |

55 |

|

2005 |

30 |

30 |

60 |

|

2006 |

35 |

30 |

65 |

|

2007 |

40 |

30 |

70 |

|

2008 |

50 |

30 |

75 |

|

2009 |

60 |

30 |

80 |

|

2010 |

70 |

30 |

90 |

|

2011 |

80 |

20 |

100 |

|

2012 |

90 |

10 |

100 |

|

2013 |

100 |

- |

100 |

Source: Agrafood East Europe December 2002

Having said that, the first tranche of guarantee funds is still larger than the 240 billion forints that are presently issued. In reality, most Hungarian farmers simply act as if there would be no change, as if there would be no European Union accession in the pipeline. In all fairness, who should they turn to?

“Hungary could not profit from her foreign market opportunities either. Endogenous and exogenous factors have equally hindered the easement of the income crisis. We must not underestimate our own weaknesses. The insufficient quantity and many times quality of products, slow adaptation, low level of sales promotion and infrastructure insufficiencies have each caused losses of profit in the millions of dollars. The effect of the exogenous factors (world market prices, world economy crises, GATT Agreement, market protection in CEFTA countries) has been cumulatively negative” (Udovecz, 2002)

Average price levels of Hungarian agricultural produce are in general lower than those of the EU 15, though there are at times exceptions such as pork and milk. This can be seen in Figures 2.4 and 2.5.

Figure 2.4: Comparison between average livestock price gaps regarding Hungary and the EU15

Source: European Commission Directorate General for Agriculture (2002), Hungary Agriculture and Enlargement, Agricultural Situation in the Candidate Countries: Country report on Hungary

Figure 2.5: Comparison between average crop price gaps regarding Hungary and the EU-15

Source: European Commission Directorate General for Agriculture (2002), Hungary Agriculture and Enlargement, Agricultural Situation in the Candidate Countries: Country report on Hungary

By simply looking at prices one can put serious question marks next to Hungary receiving the full amount of direct payments. One of the reasons for which the CAP was created was to turn the EC from a net food importer to a net exporter, a system hardly suitable for a country scourged by overproduction. Granted, nowadays this could be just as easily said with regards to the EU 15.

More importantly however, the CMO system was developed to bring the EU member states on par with the external world, and create an internal level playing field. This will be explained in the next section. With the full amount of direct payments it would in fact give Hungary an ‘unwarranted’ bonus. The same reasoning does of course not apply to the guidance funds, due to the enormous difference in structural development.

Unfortunately the bonus cannot be cashed in, for a simple reason plaguing most accession countries. These price statistics are quite misleading, as livestock prices in Hungary represent average prices across all qualities. Representing a significantly lower quality, they are compared to EU prices of the high quality segment (R3 prices, E carcasses). “The comparison should therefore be treated with care, and the price gaps for beef should be significantly lower and price gaps for pork should be consistently at and above EU levels, if adjusted for quality” (Commission, 2002). Apart from the obvious statistical problems, there is simply no demand for these lower quality products within the EU, thus being the biggest problem of all.

Of course Hungary has been hit hard by many of the problems related to transition, worldwide economic downturn and the loss of its former export markets. However, these are issues that should affect performance for only a relatively short amount of time. In reality it will only get worse as long as the structure of the industry has not been reformed to capably handle a new competitive environment.

Efficiency never was the focal point of the old administration, rather it was production output. Considering that a significant part of the sector has already vanished over the last decade, market theory would suggest the strong and efficient survive. Unfortunately agriculture is likely to face an even bigger blow than it has experienced since the transition. The farmers have continued to depend on subsidy flows, without any serious stimuli to update and streamline operating procedures. Some subsidies have been granted for the purchase of new machinery, yet this is totally insufficient when looking at the bigger picture. Ergo, many farming operations have been kept (barely) alive, but are completely unprepared for what is yet to come.

The lack of capital has led to the use of inappropriate machinery and equipment. This restricts the efficient use of inputs such as fertilizer, pesticides, high yielding crop varieties, compound feeds and others. From the beginning of transition the major source of gains in efficiency has therefore been a substantial reduction in the labor force (Commission, 2002).

A quick comparison,

Table 2.2: Production efficiency comparison between Hungary and the EU 15

|

Cereal production averages lie at an 50%-80% of the EU 15. Developments such as the Pannon wheat might change this in the future; this however does not change the present situation. |

|

Industrial crops production averages lie at 60%-70% of the EU 15. |

|

Vegetable yields lie at 30% to 50% of the EU 15. |

|

1/3 of the orchards for wine and fruits production has been neglected or abandoned, average yields are low |

|

Hungarian live stock holders produce 3-4 less porkers per sow than in the EU 15, the animal feed used is highly variable and 20% to 30% more animals die. |

|

Death and fee transformation levels are similar with sheep and chickens; all in all beef production is in the best shape compared to the other groups. |

Source: Udovecz 2002

The virtual absence of policy not only damaged the sector through lack of guidance and incentives, it has also created a huge amount of uncertainty within the farming community. Shortage of information regarding future developments has stalled capital investments, even with those that had the ability to do so. Expectancy of behavior is usually the pre-eminent requirement to create stability within a certain sector (Metcalfe, 1998).

If the sector will stabilize and recover, it will be because of foreign capital input and not so much due to internal factors.

§2.3.3 (3) CMOs

The TEC art. 32 (ex art. 38) deals with the scope of the CAP, art. 33 (ex art. 39) explains the objectives, articles 34-36 (ex articles 40-42) define the subject matter and art. 37 (ex art. 43) determines the powers of institutions. Together, these articles form the backbone for the implementation of the CAP. Since about one third of the community legislation, and about one quarter of all case law of the European Court of Justice (EJC) relates to agriculture, it is no surprise that the ‘special administrative law’ of agriculture has had a major influence on general issues of community law. In fact many important doctrines, institutional issues and principles of law have been dealt with in this manner (Barents, 1994).

Articles 34-37 only provide guidelines on what a common policy might look like, and how it might respond. They do not give a definitive description of 'the' policy or the structure of the common market organization, rather they stress the intended functional nature by referring to the attainment of art. 33 goals. According to art. 34, the institution involved has the choice to either coordinate by means of 'market forces', or 'public interventions'. Ergo, the product regimes can be distinctly different from each other in terms of approach as well as organization, yet all of them strive to achieve the art. 33 goals. Any attempts to go beyond these objectives are considered to be unlawful. Furthermore, discrimination between producers and consumers as imposed by the CMO, must be prevented at all times.

Apart from providing for structural measures, CMOs are also mandated to stabilize prices in the short term at a 'fair' level, as provided for by the guarantee funds. A wide range of possible methods is at their disposal, such as the use of levies, production controls (e.g. set aside policy), structural reforms, imposition quotas or the introduction of co-responsibility schemes. The most commonly used method is that of price intervention. Although a system of target and intervention prices is steadily losing its importance, over 70% of the total EAGGF budget is still used for DPS (direct price support) in possible combined with other measures such as quotas. Regulations do not only affect the first stage of the agro chain, but also the processing industry.

Most common prices are fixed by the council on an annual basis. They indicate the desired level at which the prices should be situated, and below or above which, other support measures should be used. At a certain percentage of this target price [0<Pi<100%], the intervention price is fixed. Below this price, the various mechanisms such as 'intervention buying' are activated.

Intervention can also occur with the aid of NTB measures. One can think of quality requirements, calendar restrictions or payment delays. For EU exporters, the gap between the intervention price and the world market price is closed thanks to export subsidies. Often, export restitutions bring the price received by domestic farmers up to the guaranteed price level. This has a number of rather unpleasant effects. First of all, it stimulates supply increases beyond what is required to satisfy demand. Secondly, it increases the input use of environmentally unfriendly products such as chemicals and fertilizer. Finally technical innovation is slowed down, since there is no pressure from outside competition. It should be noted that this model could be highly constrained. Various international agreements such as the Uruguay rounds have restricted the use of import levies. Figure 2.6 illustrates just how the pricing model operates (Ortalo-Magné, 2001).

In order to effectively use a community wide common price, a system of uniform product standards was called to life. All common prices and amounts are expressed in unity of product, using the metric system. This is linked to a classification scheme of standard qualities, where consequently lower qualities are remunerated with lower amounts of money. Not only quality matters, the marketing stage of the product is also a factor influencing the price. Since for some products harvest cycles differ within the European Union, it is sometimes necessary to set two marketing years out of sync with each other. If this happens, the concept of unity of prices loses its validity (Knubben, 2002).

§2.3.4 (3) Land reforms

Connected to this rather high level of inefficiency is the inadequate land reform process of the early 1990’s. In 1991-1992 about 2.5 million hectares directly owned by the cooperatives (thus not including the plots of active members) was auctioned off to former owners. These could be landowners who were deprived of their assets during the nationalization, or farmers who at some point had decided to leave the cooperative. Whether this process of ‘historical fairness’ was really all that justified is still a matter of debate. For one thing, Hungarians who lost their property before the Second World War were not remunerated at all, the Jewish community was especially upset about this decision measure (Pók, 1996). The fairness of the actual remuneration can also be called into question.

Those who lost holdings worth about $2000 were fully compensated. Meanwhile, ex-owners who lost farms worth $2000 to $10,000 could only claim 50 percent of their property’s value, and others who lost large estates would often receive no more than 1 percent in compensation.(Benedek, 1998)

The present activa were privatized and divided between the present and former members, making up about 15% of the national wealth (Benedek, 1998). In total about one and a half million Hungarians received just a tiny plot of land. The ‘new owners’ were banned from selling their plots, often making them what is commonly called ‘involuntary owners’. Despite this drastic fragmentation of plots, the collective sector did not disintegrate since many new owners declined to work the land and leased it to those who had worked it before.

In 1993 a deadline was fixed before which all possible beneficiaries had to make their claim known. Shortly after the process was completed, the cooperatives were no longer mandated by law to provide employment. Not unexpectedly this led to rather impressive unemployment levels in the countryside, which even now has not recovered from this shock.

A 1994 law on land ownership dramatically deteriorated the situation for agricultural undertakings. Individual land ownership was capped at 300 hectares, a ban was placed on the purchase of land by Hungarian and foreign legal persons, and the lease of land was allowed for a maximum of 10 years. The ban which is still in place was motivated by fears of foreign investors, who would buy up cheap Hungarian lands and create an iron grip on the industry. Salazar et al (1995) have argued that there is nonetheless a large speculative land market within Hungary, albeit an illegal one.” illegal property transfers disguised as renewable leases—or ‘pocket deals’ as they are known in Hungarian—and massive speculation by investors who recognized the profit potential inherent in a distorted land market.

Table 2.3: Share of Hungarian land in private use in 2000

|

Size of private holding (hectares) |

Number of farmers

|

Share of land in private use % |

Share of arable land % |

|

|

Farmers |

% |

|||

|

300+ |

300 |

0.03 |

4.6 |

2.8 |

|

10-300 |

50000 |

5.2 |

61.3 |

36.8 |

|

1-10 |

220000 |

22.9 |

27.3 |

16.4 |

|

0-1 |

690000 |

71.9 |

6.8 |

4 |

|

Total |

960000 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2000

According to Szelényi (1998) most corporate holdings were formed by the former management of the old cooperatives in the early-mid 1990s. Limited liability companies were created out of the old legal form, in this process the old debt was removed and the capital resources such as machinery and buildings were retained. This trick (ab)used the particularities of the legal system at the time as a weapon, though it reeks ‘unlawful behavior’. Real cooperatives also still exist, and again they are mostly run by the former managers.

To avoid the 300 hectares rule, collective farms can be set up together with other private farming operations, but even with ‘faked’ leases only 2500 hectares can be worked in total. This is why it is in the interest of the large farms to strive for liberalization of the internal market and to keep the foreign competitors at bay. Small farmers on the other hand fear the ‘green barons’ and possible EU competitors alike. Even though their costs have increased, a normalization of land prices would most certainly increase their problems (Papp et al, 1998) and only a very small segment of farmers would actually favor full liberalization of land sales. The EU has indeed allowed a seven-year “derogation from the general requirement to open up land markets to foreign buyers” (Agrafood, 2002). Three additional years can be added, in case ‘serious disturbances’ can be detected in the land market. Suffice it to say this will surely be the case with Hungary. Having said that, it is especially this delay that puts necessary regulatory reforms even more on hold.

§2.3.5 (3) SAPARD & AIC

It was never expected by the European commission that the new entrant countries would be able to cope with transition completely on their own. As early as 1989 PHARE (lighthouse agreement) was established for Poland and Hungary. The 1997 Luxembourg summit saw the complete restructuring of PHARE, followed by the creation of ISPA and SAPARD in 1999. SAPARD stands for Special Accession Program for Agriculture and Rural Development. It was specifically designed to prepare the Central and Eastern European applicant countries in the pre-accession phase, for participation in the common agricultural policy and the single market (SAPARD plan 2000-2006). Its specific aims are:

· Compliance with EU standards on the processing of agricultural products, including

o promoting compliance with food safety and hygienic and technical standards of the EU

o enhancing the conditions for environment and waste management

o compliance with EU animal welfare requirements.

· Enhancing competitiveness and quality

o through increasing competitiveness, technological development and improving product quality

· Enable the proper implementation of the acquis, both from a legal as well as a structural and operational perspective

SAPARD is unique in nature since it is a decentralized form of external aid, which co-finances agricultural and rural development programs emanating from the national ministries. For this purpose each government had to set up and accredit its own SAPARD agency responsible for payment and implementation of the measures approved in the program. The primary reason for this approach has been defined by the commission as follows, By decentralizing management of aid, SAPARD will give the future members an opportunity to gain valuable experience in applying the mechanisms for management of agriculture and rural development programmes […] On a broader front, the investment made now will build skills that will be readily transferable to other structural fund activities and for setting up paying agencies. It will help applicant countries as members to rapidly apply the rules applicable under Guarantee1 funded aid and to other areas of Community policy (Official Journal L161, 1999).

The following table gives an example of some of the support functions that are undertaken by the program.

Table 2.4: Rural development measures funded by SAPARD

Source: European Commission Directorate General for Agriculture (2002), Hungary Agriculture and Enlargement, Agricultural Situation in the Candidate Countries: Country report on Hungary

Originally a newly set-up institution related to the ministry of agriculture was designated as the SAPARD office for Hungary. Later on it was decided that this Agricultural Intervention Centre which as late as 1998 had still not been established, would no longer be used for that purpose. SAPARD was shifted to the MARD, whereas the AIC would serve as the paying agency for the EAGGF guarantee section. Twinning project HU02/IB/AG-03 states,

“The AIC has been entrusted by MARD to prepare itself for the function of the Paying Agency for all payments from the EAGGF Guarantee section”

The most frequently cited reason for this sudden split of responsibilities and funds between the MARD and the AIC refers to the difference between the rules of management of Guarantee and Guidance funds. The Guidance sections finances expenditures for rural development measures in regions whose development is lagging behind, as well as for the Community rural development initiative. The yearly amount of money is relatively insignificant compared to the Guarantee section financing to which direct price support belongs. Dispersion to the member states strives to achieve the CAP objectives as set out in TEC art. 33(1). For the budget year 2004 somewhere between 500 and 600 million Euros has been calculated.

A more plausible explanation for the split takes the political infighting between ministries, and the lack of political commitment with respect to creating an accredited SAPARD agency into account. Sources within the ministry have mentioned a grave lack of foresight and understanding of the functions of the SAPARD office on the side of politicians. The goal was only to create an entity that was required by the Commission, but the tasks of the program itself were not sufficiently considered.

This organizational change alone caused a number of delays with preparing for the implementation of the SAPARD program. Originally intended to be operational by October 2000, the European Commission decided to accredit the SAPARD office as late as November 26th 2002 (Commission press release, 2002).

Table 2.5: SAPARD 2000 budget available for co-financing projects

|

Bulgaria |

Czech |

Estonia |

Hungary |

Lithuania |

Latvia |

Poland |

Romania |

Slovenia |

Slovakia |

Total |

|

53.026

|

22.445

|

12.347

|

38.713

|

30.345

|

22.226

|

171.603

|

153.243

|

6.447

|

18.606

|

529

|

SAPARD annual indicative budget allocations (millions of Euros at constant prices)

Source: Commission press release IP/02/1737

Under this scheme, Hungary would now be entitled to a maximum of €38.7 million for the year 2000 and €39.4 million for the year 2001, while the indicative amount from 2002 until 2006 will be €40.6 million per annum. However there is a catch, “Payment of the first advance for the year 2000 can now be made (the maximum is 49% of the annual amount).” (Commission press release, 2002) In other words, Hungary will receive a much smaller cash flow designated for co-financing projects than originally intended. It is not going to get all the money it thinks it is entitled to, not by a long shot.

Before July 2003 the SAPARD Agency was a partly independent organizational unit within the Ministry of Agriculture and Regional Development, consisting out of a central unit and several field offices. It was a budgetary organization fully integrated into the internal structure of the MARD, waiting to be co-financed by the EAGGF and FIFG guidance funds. Only due to continuous threats from the commission and the twinning partners (Dutch and French embassies), even the smallest degree of progress has been reached. Despite numerous warnings, SAPARD in Hungary has tragically failed to perform its duties.

§2.3.6 (3) AIC revisited

The Commission has stressed the absolute importance of a well functioning paying agency. The Commission has also stressed the consequences of non accreditation and/or non compliance, which can be found in Council Regulation (EC) No 1287/95, working in conjunction with Council Regulation (EC) No 1663/95.

“The Commission being responsible for implementing the Community budget, must verify the conditions under which payments and checks have been made; whereas the Commission can only finance expenditure where those conditions offer all necessary guarantees regarding compliance with Community rules; whereas in a decentralized system of management of Community expenditure, it is essential that the Commission, as the institution responsible for funding, is entitled and enabled to carry out all checks on the management of expenditure it considers necessary and that there should be full and effective transparency and mutual assistance between the Member States and the Commission;”

In layman’s terms, no money if you don’t play ball. A developed entrant like Austria was deprived of the Guarantee funds for more than two years, thus clearly help is needed. For this reason twinning projects were called to life within the PHARE framework, to get the AIC as well as the SAPARD agency up and running. They involved making the expertise of member states available to the candidate countries through the long-term ‘secondment’ of civil servants and accompanying short-term expert missions and training. For Hungary, of the 23 twinning projects that were designed between 1997-2000, the AIC project was the only one that has yet to be started and finished (Agenda 2000, 2002 regular report). The main purpose of twinning is defined as “strengthen the administrative and judicial capacity”, which of course refers directly to the theoretical starting point of this thesis.

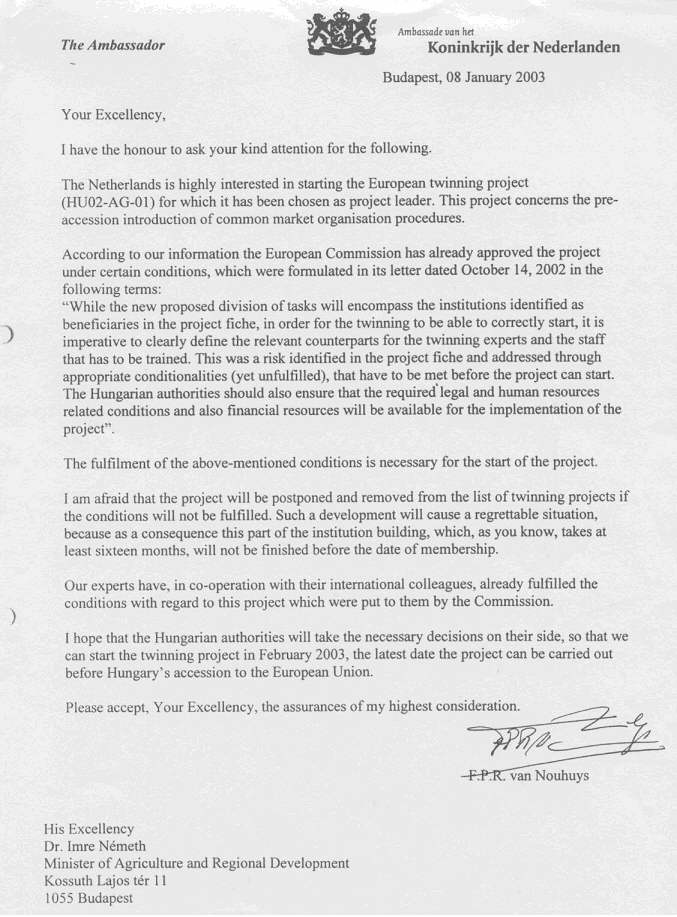

The Dutch government was designated as the partner for the AIC. Project HU2002/IB/AG/01 was scheduled to start mid 2002, which was in reality already far too late. However, the political leadership at the MARD kept delaying the project time after time. The AIC was totally understaffed, not properly funded and without the abilities to even start reforms, let alone function. Its structure can be found in figure 2.7. This situation led to the Dutch ambassador to Hungary sending what can only be described as a ‘bomb’ letter to the Hungarian minister of Agriculture, Imre Németh in January 2003 (Nouhuys). Well-informed sources have confirmed this was orchestrated in conjunction with the Commission delegates at the permanent EU mission to Hungary. The following excerpt clearly shows the severity of the situation, and can also be found on figure 2.6 on the following page: “in order for the twinning to be able to start correctly, it is imperative to clearly define the relevant counterparts for the twinning experts and the staff that has to be trained. This was a risk that was identified in the project fiche and addressed through conditionalities (yet unfulfilled), that have to be met before the project can start. The Hungarian Authorities should also ensure that the required legal and human resources, related conditions and also financial resources will be available for the implementation of the project[….] I hope the Hungarian authorities will take the necessary decisions on their side, so that we can start the twinning project in February 2003, the latest date the project can be carried out before Hungary’s accession to the European Union.”

This most certainly caused a stir at the ministry. Indeed sources have mentioned that for the first time ever since transition, a prime minister called a minister of agriculture to his office to explain the miserable handling of affairs. This is not to say the minister himself is to blame, but this will be covered later on.

Figure 2.6: Letter from the Dutch ambassador to the Hungarian minister of the MARD

Source: undefined

Figure 2.7: Internal document depicting the ‘official’ structure of the AIC

Click to enlarge

Source:undefined

The March 25th covenant mentions a starting date of July first 2003,

again a deadline which will not be reached. The AIC has only a partially

approved budget, a budget which is far too small in the first place. A second

problem is that a staff of at least 400 people has to be hired and trained. The

training alone is expected to take a minimum of 16 months with regards to

twinning, and 19 months in total. Even if the twinning would start right this

moment, this problem could not be solved since nobody seems to know where to

find these extra people, or how to pay them for that matter. The housing of the

service is quite peculiar, far too small, difficult to find and not directly

next to the ministry. Perhaps there is some symbolism in this.

The small staff which DOES work at the AIC is highly qualified and willing, but it is not up to them to obtain the required resources. In fact, quite some animosity exists between respectively MARD and SAPARD, and the AIC on the other hand. Dutch and French officials have suggested it could take 2 to 3 years before the first payments will be made, sources within the AIC have mentioned it could take as long as 4 years.

Included with each twinning project is a general risk matrix, to identify what could go wrong during the project. Though it has not even started yet, most fears have already come true.

Table 2.6: Risk matrix

|

Risks |

Materialization of risks |

|

Lack of political commitment on the part of the beneficiary institution in implementing the recommendations emanating form the project. |

• |

|

Delay in approving contracts for essential equipment or installing it (computer servers, etc.) |

• |

|

Lack of Hungarian funds to finance manpower or projects materials falling under Hungarian responsibility. |

• |

|

Failure of legislation and other documentation requiring parliamentary or official approval to be passed to the relevant institutions (e.g. parliament) in time. |

• |

|

Feedback on workshops and training from either participants or experts making presentations are not on time. |

Not Applicable |

|

Resource problem arising from under-funding of activities. |

• |

|

Availabilities of short term experts on behalf of the EU, resulting in activities being postponed. |

- |

Source: Covenant EU PHARE Twinning Project HU2002/IB/AG/01, final version 1.1 March 25 2003

§2.3.7 (3) European Agricultural Guarantee and Guidance Fund Paying Agency

On May the 12th legislation was passed that joins the SAPARD office and AIC into a single new paying agency, temporarily dubbed the Agricultural and Rural Development Agency. Its legal creation was scheduled on July 1st 2003, and the structural scheme can be found in figure 2.8. The organizational structures of the existing offices will not be completely fused, but to some extent co-exist next to each other. What was not operational under the old institutions, such as the CMOs, will fall directly under the responsibility of the new management. Because it is intended to be an independent institution, it has been slated with its own back offices such as internal audit, Human resources and a legal department. At present none of these exist however.

The main difference will then be a unification of leadership, a ‘new’ leadership. Although there is a rationale behind this, at present it is much too late to make such changes which are essentially only part of a power game played by the ministry. This at least is the view reflected by the AIC staff.

In the final covenant version, signed on the 14th of April, a project office for EU institutions was designated as the leader for this merger operation. “The management of the project office is responsible for creating a new central agricultural authority to be established by July 1st, 2003 through the amalgation of the Agricultural Intervention Center and the SAPARD agency”. Due to this co-existence rather than fusing, the twinning project has not changed significantly content wise. What HAS changed however is the project beneficiary, which as of April was no longer the AIC but the MARD.

The project office was created in the wake of the last election victory, especially for the purpose of guiding the creation of a single paying agency. In order to work more efficiently, the head of the office reports directly to the administrative state secretary and the office was granted a fair amount of special powers to work across functional lines and departments. Its existence was never put into legislation and to this day it officially does not exist.

Figure 2.8: unofficial structural lay-out of the Agricultural and Rural Development Agency

Click to enlarge

Source: undefined

As easy as it started its work, after September 2002 its rising star began to fade as a result of a decrease in political commitment towards its task. The usual problems such as understaffing and insufficient resources has led to a staff of only 15, many of which were taken from the AIC staff because of their expertise. After July 1st the office merged together with the AIC and SAPARD agency to form a new entity, thus becoming the third player. Sources within the office have expressed their belief in the creation of a functioning new entity by May 2004, provided the political leadership is willing to give all the necessary resources and is able to elevate its managerial skills to the next level. When asked how realistic these last assumptions really were, the answer was, - it could go either way.

On May 30th the rumor was launched that a special commissioner from the prime minister’s office would be appointed as a liaison to once again increase the PO’s capabilities. The minister himself was quoted on saying that inaction on the paying agency could have dire political consequences, such as a loss of the next elections. Still, the incompetent handling of the twinning project shows that this does not necessarily will entail significant improvements.

Not all employed at the SAPARD office, especially the AIC, shared the project office’s view on its duties. Some felt that the notion of an independent agency was somewhat of a farce, as the project office had already been issuing orders to the AIC regarding subsidy payments. A senior official was quoted in June as follows, “We have been stripped from our competencies and responsibilities. Now we are just an understaffed administrative enforcement mechanism”. The fact that neither the AIC president, nor the SAPARD president were ordered to lead the reorganization was perceived as an ominous sign. The fact that both departments were forced to sign over some of their staff caused even more resentment. With a history of being faced with disappointment and unnecessary setbacks, the cynical and unbelieving attitude is only natural. The author has obtained from inside the ministry a classified governmental decree delineating the relationship between the ‘independent office’ and the MARD. Article 6 in this document confirms the power coup of the MARD. The full decree can be found in the appendix.

Article 6

(1) ARDA is headed by the President appointed for an indefinite term and dismissed by the Minister.

(2) The Vice President of ARDA is appointed and dismissed by the Minister on recommendation from the President of ARDA.

(3) Employer’s rights over the President of ARDA are exercised by the Minister. Employer’s rights over the Vice President of ARDA are exercised by the President of ARDA, save for appointment and dismissal.

Obviously this does not conform to the nature of the twinning, which defines the PO’s responsibilities as follows,

Table 2.7: Responsibilities of the PO

|

Elaboration of the organizational structure of central and local PA offices |

|

Change management |

|

Elaboration of procedures and process description for authorization |

|

Elaboration of the procedures and the process descriptions for physical control methods |

|

Competency profiling |

|

Supervision of the database creation and update |

|

General development procedures for market regulations |

|

Ensuring IT security |

|

Preparation for supervision of external audit processes and procedures |

|

Elaboration of the procedures and process descriptions for IT supporting the implementation of agricultural market and trade measures |

Source: Covenant EU PHARE Twinning Project HU2002/IB/AG/01, final version 1.1 April 14 2003

In short, projects have once again been delayed, top managed has been ‘purged’ and transparency has been reduced even further. Schedules can be fixed, what is more troubling is the apparent inability of the various agencies to cooperate in a friendly and efficient manner. Each has their own take on affairs, and there seems to be little convergence between opinions. Whether the PO could prove its counterparts wrong really depends on the leeway and resources it would be granted, and what kind of cooperation it would be likely to encounter. As of yet, there is still no financial controlling institution set up with regards to the new agency, and no unified, let alone approved budget. If history is any predictor of the future, it will be a gloomy one. A breakdown of the system, with politics as the main culprit.

§2.3.8 (3) Other departments

The process of continuously changing organizational positions of departments does not help to create a well functioning ministry. In fact, it has become somewhat of a sport to make these changes on an almost weekly basis, leading to no positive consequence whatsoever. The current minister was ordered to draft a completely new organization lay-out for the ministry, however it is unclear who is involved in the process. In any case, even if the task would be completed in a relatively short amount of time, two essential obstacles remain. First of all, to get parliamentary approval. Secondly, the expected life span of the minister. Ministers of agriculture don’t tend to exceed one year of service, and it is rumored the present one will face resignation within the next 6 months.

Finally, there is less than meets the eye. Some of the departments listed on the official organogram only exist on paper, or are so ill equipped they are not able to function. The newly formed food safety agency is a perfect example of this. Being a priority of Community policy, at present yields one single office and a single secretary. Needless to say that does not satisfy operational requirements.

Obviously there is a lack of ‘sense of mission’. It is a result of historical, political and ‘cultural’ factors, and clearly change will be very hard to achieve. Effective policy making capabilities were, are, and at least in the near future WILL be negligible.

§2.3.9 (3) EMS

The author has managed to acquire an unpublished report of the ‘Evaluation and Monitoring Services of PHARE’, who views “are those of the EMS consortium and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission”. Although the report dates back to July 10th 2002, it still holds its validity on many counts and can be considered as the most accurate depiction of reality from an ‘outside’ institution. The 2003 update is currently in the making and as of yet has not been issued. Because these reports are not published or directly cited by the commission, they are void of political ‘smoothing’ and thus perhaps harsher with critique. The evaluated programs concern:

Table 2.8: EMS program fiches

|

Programme component |

Title |

Start date |

Expiry date |

|

HU-9909 |

Agriculture |

03/11/99 |

30/07/02 |

|

HU-0003.01 |

Animal health |

12/09/00 |

30/09/02 |

|

HU-0102.03 |

Veterinary and phytosanitary acquis |

23/05/01 |

30/11/03 |

|